Chief Communication Officer Magazine for Communication Leaders

Contents

1. Introduction By Professor Sam Black

2. The Intellectual Base Of Public Relations

3. The Public Relations Function And Its Parameters

4. Recommendations Regarding Teachers And Faculties

5. The Dialogue Between Academics And Practitioners

6. Research – Pure And Applied

7. Evaluating The Effectiveness Of Public Relations

8. Recognition

9. Recommendations

Internationally, few professions have rigidly standardized educational syllabuses but all have generally accepted educational standards and requirements.

For over 60 years public relations education has been developing in universities and colleges in many countries but until recently there was little attempt at coordination. There is now a keen desire to achieve some harmonization of educational standards and a consensus has developed.

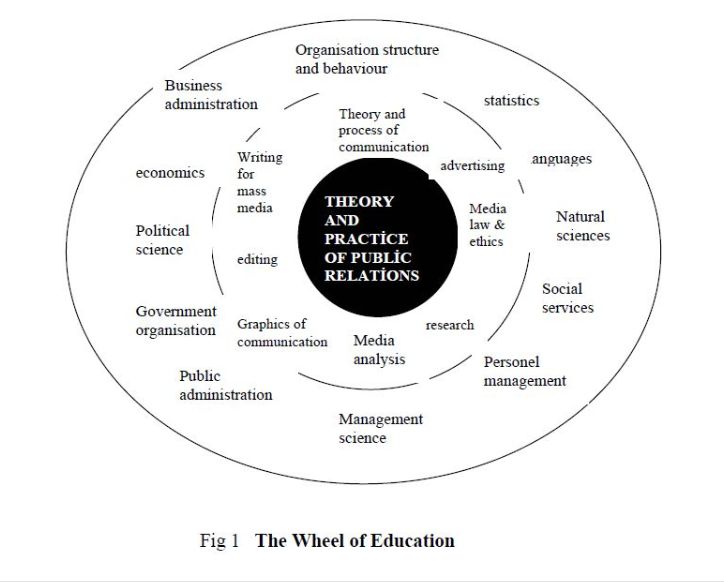

The curriculum for the education of a student wishing to enter the profession can be pictured as a series of three concentric circles. The smallest central circle encloses the subjects specifically concerned with public relations practice. The second larger circle has the subjects in the general field of communication. The third and largest circle represents the general liberal arts and humanities background, which are essential preparation for a successful professional.

One of the principal objectives of the International Public Relations Association (IPRA) since its inauguration in 1955 has been the encouragement of public relations education worldwide.

In recent years there has been a steady development of public relations education in many countries and this process has been accelerated during the last few years through the publication and dissemination of IPRA Gold Paper No 4: ‘A Model for Public Relations Education For Professional Practice’ published in January 1982.

In 1980 IPRA decided that the time was opportune for a systematic study of the state of public relations education, as it existed in different countries and to make recommendations for the extension of public relations in the field of education, professional developments and professional standards.

This study, which was carried out over a period of fifteen months, resulted in the publication of Gold Paper No 4 which was presented at the Ninth Public Relations World Congress at Bombay in January 1982.This report was the work of an international group of IPRA members under the Chairmanship of Göran Sjöberg, of Sweden.

Gold Paper No 4 has been used by IPRA members in many countries to support approaches to higher education institutions to introduce public relations education programmes. These negotiations have resulted in the introduction of many new courses, such as the full time MSc degree programme at the University Stirling in Scotland.

The parameters of the public relations function constantly change to take account of political, social and technological developments and other changes that affect companies, organisations and official authorities and thus their public relations challenges, opportunities and problems.

The training of the students for the public relations profession implies curricula and internship that equip them for the kind of future environment they will be working in, not that which exists today.

In considering the elements of public relations education it is essential always to respect the individual nature of a country’s culture and historical background. The theory of public relations is valid everywhere but its practical application must take to account national character, economy, religion and environment.

IPRA’s role, as exemplified by the production of this new Gold Paper, is to synthesise the experience of different countries and to encourage national public relations associations to adapt the best examples from other countries to the formation of national public relations educational and professional advancement programmes best suited to their milieu.

This Gold Paper does not purport to be the one and only key to success in setting up worthwhile public relations programmes at higher education. It should, however, provide a point of departure for discussions between university bodies and public relations associations on the improvement of educational facilities and curricula.

This Gold Paper is confined to education and training so the important subject of ethics and professional conduct is not dealt with. This will be the topic of IPRA Gold Paper No 8.

All IPRA members are bound by the code of Athens- a code of ethics based on the UN Declaration of Human Rights –and by the IPRA Code of Professional Conduct, which regulates member’s behaviour and attitudes in their practice.

We know that this Gold Paper is not the final destination but merely a further stage in a long journey on the road leading to improved standard education in our expanding profession.

Thanks are due to many IPRA members and other public relations academics and professionals.

London, September 1990

Sam Black Chairman, IPRA International Commission On Public Relations Education.

2. THE INTELLECTUAL BASE OF PUBLIC RELATIONS

Scholars have insisted for more than three countries, that one of the major characteristics distinguishing professions from occupations is the intellectual base of the former. For several decades there has been global evidence that effective public relations practice requires knowledge, skill and intellect. Public relations education is based on a solid body knowledge that continues to develop and expand.

Public relations is founded on an intellectual base, as are more traditional professions such as medicine, law and the clergy. Each year, with continued developments in the study and understanding of public relations theory, practise and research, our field increases in depth and complexity. The breadth and volume of these developments has been such that current knowledge in public relations is also vast university educational programmes in the discipline are not always in sharp enough focus.

For the purpose of report, we consider public relations education to consist of not just public relations courses alone, but of study in all disciplines linked to the demands of the practice. Public relations have been thought at many universities throughout the world seven decades. However, we find it is more difficult to conceptualise public relations education than it is to understand education in other disciplines that have richer historical connections. Such areas would include the sciences, arts and letters as well as the education in more traditional professions.

Throughout all of the traditional professions educators and practitioners have realised students require a broad liberal education in the sciences, arts and letters before they begin education for professional practice. Eight years ago, in IPRA Gold Paper No 4 we suggested that the time had come for public relations to move to the postgraduate level as is the case in most countries for professional education in law, medicine, and other highly respected occupational fields.

As such we recommended that those who intend to study public relations at universities should first obtain a general liberal education. We believed that placing the trust of education in our field at the postgraduate level would also raise the intellectual quality of public relations itself.

In suggesting that public relations education, ideally, should be provided mainly for those students who already have received a first university degree in other fields, such as commerce, sociology, psychology and journalism, our intent was not to depreciate the value of undergraduate (first degree) level programmes that teach public relations However extensive research for Gold Paper No 4, led us to identify reactions from the European Confederation of Public Relations (CERP), the US Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) and the Educators Section of the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) that stressed the belief that public relations education was most effective at the post graduate level. Reactions from educators and practitioners in Federal Republic of Germany, The Netherlands, Great Britain, Canada and other countries confirmed this same point of view.

Since Gold Paper No 4 was distributed, there has been prolific development in public relations education beyond the basic bachelor’s degree. Despite this development, which has taken place in all corners of the world, public relations education still needs some coordination of educational standards. In this report we reiterate the recommendation that public relations education should be based increasingly at the postgraduate level. One major goal of this document is to stimulate discussion and action that might lead to some measure of international consensus concerning educational standards for degree level programmes in public relations.

Although there is general theoretical agreement concerning curricula for public relations education, there are differing schools of thought about the purpose of programmes in our field. One is the idea that these programmes should be technician-based communication skills programmes that are very similar to many basic first degree (bachelor’s) programmes. The other suggests these programmes should go beyond the skills approach and prepare students for roles as counsellors, managers, decision-makers, and so-forth.

This school of thought recommends the study of communication and organisational theory, statistics, research methodology, public relations management and administration, and so on.

With this second school of thought it usually is assumed communication skills education is a necessary prerequisite to postgraduate study, but the preference is to have students receive this skills learning in the first-degree programme or else as extra work before entering more managerial-based postgraduate programme.

A concern with the development of postgraduate programmes is that far too many continue to be administered not by public relations faculty but by faculty in journalism, psychology, commerce, advertising, marketing, management or related fields. Many universities claiming to offer public relations degree programmes have merely one or two qualified faculty members. We continue our recommendation that this must change before public relations education can achieve the status it deserves. While we find no objection to having experts in these areas teaching in public relations degree programmes we recommend strongly that curricula be built around the IPRA Wheel of Education.

Unfortunately, there are times when public relations becomes a small spoke in the wheel of education for a related discipline.

As we have done in the past, we recommend that solid public relations degree programmes be developed and nurtured at leading universities, and until such time as there are adequately qualified instructors, we caution against creation of public relations programmes at every university. We continue to view with some alarm the proliferation of universities proclaiming their competence in public relations teaching and research without adequate resources–such as faculty, administrative support, research facilities and research travel budgets.

We also recommend firmly that steps be taken to build on the tentative efforts of some University business and management schools to incorporate public relations as part of the education and training of general managers. Practitioners should also be encouraged to see higher level management qualifications as important, if not required additions to their qualifications as senior level management advisors.

As public relations education continues to develop at the postgraduate level, we are compelled to express our concern about the continued shortage of doctoral programmes that truly emphasise public relations. Without these PhD programmes we will not develop the academic scholars and applied researches necessary to provide qualified faculty for university based public relations degree programmes. These doctoral programmes also are necessary to help upgrade the intellectual characteristics of public relations.

Of course we continue to believe research and the practice itself must take considerable contributions in this regard. Academic programmes should undertake research thus making scholarly contributions to the literature of the field. At the same time. Practitioners should be willing to find ways to share information about their own research methodologies without revealing proprietary information gathered for clients.

We must continue to try to strike the correct balance between theory and the need for public relations practice based upon solid, empirically tested foundations and concepts.

3. THE PUBLIC RELATIONS FUNCTION AND ITS PARAMETERS

Professional public relations operates in every sphere of life:

1. Government–national, regional, local and international.

2. Business and Industry–small, medium and transnational.

3. Community and social affairs.

4. Educational Institutions, Universities, Colleges, etc.

5. Hospitals and Health Care.

6. Charities and good causes.

7. International affairs.

Public relations practice is:

1. Counselling based on an understanding of human behaviour.

2. Analysing future trends and predicting their consequences.

3. Research into public opinion, attitudes and expectations and advising on necessary action.

4. Establishing and maintaining two-way communication based on truth and full information.

5. Preventing conflict and misunderstandings.

6. Promoting mutual respect and social responsibility.

7. Harmonising the private and the public interest.

8. Promoting good will with staff, suppliers and customers.

9. Improving industrial relations.

10. Attracting good personnel and reducing labour turnover.

11. Promotion of products of services.

12. Projecting a corporate identity.

13. Encouraging an interest in international affairs.

14. Promoting an understanding of democracy.

A typical public relations activity will have four parts:

1. Analysis, research and defining goals and objectives.

2. Drawing up a programme of action.

3. Communicating and implementing the programme.

4. Monitoring the results, evaluation and possible modification.

It is obvious that public relations requires a wide range of skills and experience. It is essential, therefore, that public relations professionals should possess the qualities, which will deserve universal recognition.

The aim should be greater recognition by industry, government and other institutions of the true role of public relations but ultimately we can only gain that by our actions. We must prove our value by the development and publication of case histories worthy of our professional aspirations.

Increasingly, business leaders and politicians are recognising the full potential value of effective communication, even though some fail to attribute it to public relations effort. One problem is our inability to ensure that we are always consulted at the planning stage and allowed to make a positive contribution to solving the problems of top management. Furthermore, the role of public relations overlaps with other management functions such as planning, marketing and personnel, leading to territorial problems.

Everything has potential implications for the public relations function, from interpersonal thorough to mass communication. Information is power: it is instantaneous, global, more technical and complex which behoves practitioners to use it wisely. Information is fast becoming the new unit of currency.

The role of practitioners is to assist employers in the management of information and of change and to transform fear of change into productive opportunities that contribute positively to society and the individual at global and local levels. This is in vast contrast to earlier days when planning was predictable. If we cannot add to our communication skills sensitivity to rapid innovation and radical structural shifts, we will not make contribution we should.

Matters are made more difficult by the amazing advances en communication technology, which have turned the traditionally distinct areas of voice, vision and graphics into simultaneous and instant transmission of all there. When people can see and talk to one another, share the same reports and charts without leaving home or office, and then the ‘Global Village’ has really arrived. True public relations professionals appreciate such evolution and transform it into positive contributions for their employers and society.

In these matters, however, public relations, professionals meet several paradoxes. To begin with, the ‘Global Village’s’ instant sharing of information is coupled with a need for more and more face-to-face contacts. And, at the same time, markets are more segmented and fragmented (see e.g., the vast number of regional and special interest magazines alongside international media knowing to national boundaries).

A second paradox: public relations, dealing with human relations, includes dealing with human communications. Public relations professionals should be aware of the fact that multiplying communication techniques and media does not automatically mean multiplying communication as a fundamental aspect of human existence, in the sense of understanding and sharing.

Organisations can no longer rely on secrecy and resort to ‘no comment’. On the other hand, they can turn a duty to be accountable into an opportunity to gain a sympathetic listening response. In short, to use their right to communicate in the most effective way possible whether promoting a product or a philosophy.

Whereas previously top management spent some 80 per cent of their time managing their organisation, possibly 10 percent communicating and the remainder at leisure, now the proportions are changing as communication is becoming so demanding. Environmental concerns have become a major pre-occupation of most chief executive officers.

To public relations managers, this implies that their future depends on staying ahead of senior management’s needs: they must keep looking at the next area of concern, translating today’s issues of concern into future opportunities by injecting this knowledge into corporate policy consistent with public opinion and translating it into public relations programmes of action.

Public opinion today may be sceptical of authority and more discerning but it seeks more management not less, not just more care over sales and profits but also over natural and human resources, i.e., more concern about environmental pollution and conservation, consumer health and employee safety. People want more disclosure of financial data, closer links between the private and public sectors, and greater fairness in the use of the free market. People want access to information so that they can ask ‘why’, ‘why not’, and so that they can participate.

Public relations practitioners are the eyes and ears of management. They should be able to coordinate with other functions: law, finance, marketing and personnel, and to use the most cost-effective means of reaching various audiences.

Our challenge is to be anticipatory and to be central to decision making. The role of public relations as detector, evaluator, interpreter and communicator becomes ever more important with the growth of more groups and institutions representing different interests across the world. Dealing with this diversity of people and interests demands great skills and sophistication, and growing specialisation increases the need for broad understanding – to be generalists in the age of specialists.

The ability to comprehend overall organisational strategy, corporate policy, the marketplace, and the external environment, is vital.

Public relations will either become recognised as indispensable to the vitality of all organisations or it will be relegated to merely carrying out a useful range of techniques. All public relations education needs both a solid base in scientific approach and a society-oriented, forward-aiming emphasis. Only such a combination will produce students of public relations capable of filling professional jobs at management level.

4. RECOMMENDATIONS REGARDING TEACHERS AND FACULTIES

There are substantial differences in the qualifications of public relations educators throughout the world. Too many public relations courses are taught by people with inadequate experience in both academic and professional areas.

With that in mind, we offer the following suggestions regarding those who should teach, who instructs these teachers and where public relations should be taught.

Qualifications of Teachers

We are convinced that public relations courses should be taught by individuals with a sound experience and understanding of both the academic and professional aspects of the field.

In view of the importance of research to a true academic discipline, it is desirable that in order for public relations to be accepted as such a discipline worthy of ‘graduate school status’ at major universities, members of faculty hold PhD degrees, or comparable academic qualifications, and, as part of their employment, be expected to conduct research adding to the body of knowledge of our profession.

It is also essential that in addition to their academic qualifications those who teach public relations should have considerable practical professional working experience in the field. We also strongly recommend them to continue to develop their professional experience while they hold teaching appointments.

There will be exceptions where suitable teachers will come direct from the practice and substitute lengthy and appropriate years of experience for academic credentials. Of course, specialists are needed from other disciplines in public relations courses, like lawyers, psychologists, sociologists, scientists, economists and linguists.

Ideally, all professors of public relations would have the appropriate academic credentials combined with many years of experience working as practitioners. This ideal situation will not always be possible.

Consequently, many faculties comprise individuals with the necessary academic requirements and others with solid professional experience. Professors of public relations, however, should be qualified, willing and able to teach, to undertake research and to provide service to the profession of public relations and to society itself.

Young lecturers cannot be expected to have many years of practical experience and teaching but they should be expected to register for advanced degrees.

The concept of an ideal public relations education situation should never ignore the present reality of public relations education in some countries. For various reasons, public relations education does not exist in many countries. In these cases, the national public relations association should give priority to the establishment of education at ‘grass roots’ level before seeking public relations sequences at academic level.

Who Teaches the Teachers?

The members of the Commission expressed concern at the small number of universities equipped to prepare public relations faculty members in line with the aforementioned requirements and recommendations.

Those who teach public relations should, wherever possible, receive a PhD degree, or at least a master’s degree, at universities where there exist public relations scholars under whom they can study. Some teachers will benefit from considerable course work, and perhaps even degrees, in related fields such as commerce, psychology, sociology, journalism, communications, political science, and so forth, but ideally these studies will be conducted under the supervision of a public relations specialist.

Universities are not the only places where public relations teachers can gain the desirable professional experience. Practitioners have an obvious interest in ensuring that those who teach public relations remain adequately informed about our profession. In addition to liaison activities between scholars and practitioners, and in addition to the use of guest lecturers from the profession in university-based instruction, practitioners should do everything possible to keep professors updated on developments in areas such as case studies. Budgeting, research methods and so forth.

Also, public relations educators associated with better organised programmes in the more developed countries should be encouraged to train and advise those teaching public relations in developing nations.

We are very happy to see that IPRA’s efforts to stimulate meetings for teachers in different continents have been very successful.

Both in the USA and in Europe there have been many meetings of academics and professionals with the objective of studying teaching methods and discussing optional ways of organising public relations education.

Where Should Public Relations be taught?

In the light of interdisciplinary nature of public relations and of philosophical differences between universities in different countries it is obvious that public relations education programmes will continue to be situated in a variety of academic ‘homes’.

We do not wish recommend any specific home for the discipline and caution against recommending that ‘Schools of Public Relations’ be established, for the real public relations school is the entire university itself with its diversified facets of knowledge. We do, however, recommend that public relations be taught as an applied social science with academic and professional emphasis.

Although public relations is taught at the undergraduate level in many parts of the world, this IPRA Gold Paper recommends that efforts be made to establish public relations courses, programmes and curricula also at the post-graduate level, which for international purposes is defined as study beyond the first and/or baccalaureate degree. For countries with different University systems this means in the second phase of the doctoral programme or the second licentiate (after 3 or 4 years). We recognise that depending on the education systems in different countries, public relations could be offered as a complete University curriculum of 5-6 years (the implicit model) or as part of (on top of) a complete curriculum (explicit model).

We envisage students of public relations as those who have mastered the university entrance qualifications of their respective countries when they are approximately 18 years old, after which they will study in an undergraduate programme for three to five years. Some of these students might study the arts or public relations, others politics, commerce, journalism, law or the sciences.

When they have successfully completed their undergraduate degree programmes, they could be accepted into the graduate level programmes in public relations, which would lead to Master’s, and PhD degrees in the field.

This would place education for public relations at the same level as many of the more traditional professions–for example, medicine and law.

It is important that the public relations subjects should be part of the curriculum of study of other professional fields and other academic disciplines (as minor options) to ensure an understanding of the importance of public relations in today7s society. For instance, law school students could benefit from public relations courses and students of business and administration should understand how public relations concepts fit into the strategy of management.

However, we strongly recommend that such instruction be given by qualified public relations faculty or public relations professionals acting as visiting faculty and we caution against law schools, business schools, and other professional programmes teaching their own courses in public relations without professional assistance.

Support for Public Relations Education

Two major types of support are necessary for public relations education to be effective. One is maintenance and sustenance from the academic institution offering the courses and the other is backing and advocacy from public relations practitioners.

Throughout the historical development of all traditional professions–i.e., medicine, law, the clergy–one finds considerable professional support for higher education from the professions and from universities. In order for public relations education to be successful it also must receive this type of enthusiastic support.

Practitioners can encourage the development of public relations degree programmes in number of ways.

First and foremost practitioners must believe in public relations education and be advocates for its development and growth.

In addition, practitioners can assist public relations education by proving internship opportunities for students, serving on advisory boards of public relations departments and programmes and by working with educations committees of the various public relations societies such as national organisations and IPRA.

When possible, practitioners should be involved in dialogue with educators concerning curriculum development and research. In some situations practitioners also can assist programmes in fund raising and development.

Support from academic intuitions also is essential. Unfortunately many university-based public relations degree programmes are understaffed and forced to operate on less than adequate budgets.

After careful study of a number of existing public relations programmes at universities throughout the world, it is clear that a university should not attempt to begin teaching public relations unless it is prepared to provide sufficient resources. Ideally, a university should have at least one full-time faculty member for every fifteen to twenty public relations students. In addition to proving these faculty positions, universities also should make certain the financial resources are there for secretarial and office staff, space, equipment, library, computer and travel needs of faculty.

Public relations faculty will need to maintain professional relationships with both academic and practitioner societies and we encourage universities to acknowledge this when planning travel and professional development budgets.

Public relations also should be treated with dignity by other disciplines and faculties within the university. Unfortunately, this always is not so.

In an earlier chapter we commented that public relations education programmes will continue to be situated ‘in a variety of academic’ homes. Although we do not wish to recommend any specific home for public relations, we must insist that public relations be treated with respect wherever is resides.

All too frequently, public relations degree programmes have more students but fewer faculties than other emphasis areas in the home department. If universities are willing to accept the

revenues generated by having the often-popular public relations courses they should be willing to provide adequate funding for such programmes.

We believe it is important to encourage student societies at college and commend the practise of setting up student public relations consultancies, which operate as independent agencies.

Continuing Education for Practitioners

We recommended progressive approach to programmes of continuing education and professional advancement for those working in public relations. Such programmes could be developed within IPRA and the various regional and national public relations professional associations and should provide educational opportunities for practitioners at various levels of expertises and experience.

These educational opportunities should be both technical and theoretical in natural and should branch out into related disciplines as well as providing refresher course opportunities in areas of public relations, such as applied research, which constantly change.

These courses might be conducted in cooperation with management associations, university extension programmes, or other appropriate bodies. Programmes of this nature have been initiated in the USA and in other countries.

Management Education for Practitioner

Public relations is a management function and, as much, should be included in the management curriculum of University and other business and management schools. Properly dealt with these settings, public relations would be appreciated and seen in context by managers taking Masters Degrees in business administration (MBAs) and other management qualifications.

Practitioners should be encouraged to look to the business and management schools for preparation- though degree, executive development and other courses-for practise at the most senior management levels.

Efforts should be made to build links between schools of communication, offering programmes in public relations with schools of business and management, to develop qualification appropriate to practise in this area of management.

5. THE DIALOGUE BETWEEN ACADEMİC AND PRACTITIONERS

The relationship between educators and practitioners in public relations is very important for the future success of the profession. In this respect, there are five elements:

1. Dialogue between academics and practitioners in general;

2. Contribution of practitioners to training programmes and curricula;

3. Position of internships (or placement) in training programmes;

4. Relation between the (academic) teachers and practice;

5. Possibility of teaching professional practice aspects in the curricula.

1. Education and Practice

There are many possible answers to the ideal relationship between education and practice. It is public relations thinking to create harmonious relations wherever possible, but we must be wary of apparently plausible solutions. Reality shows that the development of education programmes on the hand and rapid development of both generalisations and specialisations in the field of practice on the other demands a continuous dialogue and cross-fertilisation.

This dialogue would be improved if extreme attitudes could be rejected: elitist teachers claiming the total responsibility in their own field without any interference by practitioners and elitist practitioners demanding training that is 100 percent devoted to practical situations. It must be clear that these disparate points of view harm the education of young people what seek a career in public relations practice.

The future of public relations education and training and therefore the future of the profession depend on the extent to which a satisfactory dialogue is developed.

2. The Practitioner’s Contribution to Training

Public relations practice and the training for it are two fields with quite different responsibilities. Training and teaching is a profession as is public relations practice. All concerned must learn to cooperate fully.

Inviting professional practitioners to participate as guest lecturers is an excellent way of achieving this contact. Competent practitioners are not, however, always-competent teachers. Sometimes they assume students have more knowledge of the practical problems of the profession than they possess and this can be a hindrance to successful teaching.

A better solution might be to invite the assistance of only a few practitioners and for a longer period, say, a week, in which they can discuss complete projects and cases with students.

There is another way for practitioners to contribute to training programmes. Several universities invite practitioners to ‘adopt’ groups of students and to guide them for a longer period while they carry out limited research or case projects supervised by these practitioners. This adoption system could be an efficient instrument in reducing the distance between education and practice.

3. The Importance of the Internship or Placement Period

A very effective method of bringing students into contact with the profession is the internship or placement system. It should be pointed out, however, that experience in this kind of arrangement is not always successful. There is often a lack of adequate briefing by the supervisors of trainees and therefore the opportunity offered by internship is not sufficiently exploited.

Furthermore, some practitioners lack the willingness to spend sufficient time and attention to supervise the students.

The nature and substance of the internship term should be given high priority on the agenda of the dialogue between education and profession.

4. The Relationship between Teachers and the Profession

From the different reactions to Gold Paper No 4 it can be gathered that some trainers, those on the academic level, have created and elitist distance between themselves and the profession. This attitude is objectionable, but not incomprehensible if one takes into account the other extreme of the demands of the profession, which seek to define the subjects for tuition and to control the training.

That standpoint, too, has to be rejected. Teachers have their own responsibilities and cannot be unduly dependent on the profession. Concerning the theory of public relations, standards other than those dictated by the profession prevail. Scholars have a duty to lay a scientific foundation for theory, supported by independent analysis and research.

It is strongly recommended that teachers must have acquired practical experience as well as academic training and that they keep in contact with daily practice by consulting or doing some planned public relations assignments in addition to their teaching activities. Sabbaticals also provide an opportunity for renewal of professional experience.

5. The Methods in Education Programmes

There is a difference of opinion as to the extent to which it is possible to educate young professionals so that they can function efficiently in the profession immediately after finishing their university training.

It is usual to provide a measure of practical experience during the academic course so that a newly qualified young practitioner will not be too unfamiliar with the real world outside. Perhaps we could call this ‘how to’ training, for convenience.

Another approach is to consider that real experience can only be learnt through actual working in the profession. This type of education lays much more emphasis on introduction into the scientific background, on analysis and research–the ‘why to’ and the ‘how to think’ approach. The exponents of this kind of education claim that a graduate trained in this way can be employed successfully immediately after graduation and will gain the necessary experience very quickly.

The ideal situation, however, is likely to be where the ‘how to’ and the ‘why to systems are linked together in the curriculum.

Considering the future of public relations practice, which undoubtedly will be of a pluralistic nature and will demand generalists as well as specialists, we have to beware of training which is too narrow, which will be out of date in a few years and which will limit the usefulness of young graduates.

On the other hand, people should not leave the university without having acquired a critical sense, solid knowledge of research and an awareness of social change and its implications on society, industry and organisations in general.

Recommendations and Conclusions

1. It is advisable that national public relations organisations, through their education committees, should encourage as much variation as possible in the training programmes offered.

The needs of those wanting to follow a short, simple practical course without any academic ambitions should be considered. Others may have a purely scientific interest in public relations but do not wish to be trained for practice. Finally, there are those who wish to follow a different vocational training or university study, but who regard some knowledge of public relations as necessary for their future success.

2. It is neither possible nor desirable to offer only a single model for the ideal balance between public relations practice and training.

The analysis in this chapter aims to offer a practical basis for the discussion which will undoubtedly manifest itself strongly, as training in public relations develops and the profession makes greater demands on young entrants.

6. RESEARCH – PURE AND APPLIED

Introduction

Before we discuss the complicated field of public relations-related research, we should carefully discern several types of research and several subjects of research.

Research, as it is commonly understood in the scientific area, is of two general types: ‘pure or fundamental’, ‘basic’ research’ and ‘applied research’.

In the ‘nard’ sciences, pure or basic research devotes itself to an examination of natural phenomena in an effort to find the answers to what happens and why it happens. Applied research tries to take the lessons or principles that have been developed as the result of pure research and put them to work in the conduct of human affairs and in ways that will improve the human conditions, as in medicine, manufacturing, or construction.

Insofar as public relations is concerned, ’ basic research’ is of the type conducted by sociologist, psychologist and other social scientist who try to discover how human beings communicate and interact. It should be noted, however, that research in the social sciences seldom produces the same kind of definite statements of principal that are evolved in the ‘hard’ sciences. Ideally, the lessons that the social scientist learn, the principles they develop, should be applied by public relations professionals in their programmes for their managements or their clients.

But, this is not always the situation. In fact, it is very seldom the situation. For one thing, the ‘laboratory’ experiments that social scientist may conduct under controlled conditions are often difficult or impossible to duplicate in the real world of every experience. Additionally, many public relations people are not informed about developments in the social sciences and often do not consider research as a tool for developing their public relations programmes.

We should recognise the following types of research:

1. Research, initiated and elaborated by industries or non-profit organisations.

2. Research initiated by industries or organisations, elaborated by research institutes or universities.

3. Research initiated by universities or research institutes, supported by industries, organisations or government.

4. Research initiated by universities or colleges, merely for scientific or education reasons.

5. Research initiated by individuals (preparation of theses) supported or sponsored by universities, governments or private organisations.

Some examples of ‘fundamental’ research are:

1. Communication–network research.

2. Philosophical analysis of communication.

3. Linguistic analysis of public relations texts.

4. Attributor research (closely connected to identity–and image-research).

5. Cultural-anthropological-based research in organisation’s cultures and identities.

6. Research in scientific presuppositions of image–research.

7. Research in moral behaviour and ethical preconditions in the public relations profession.

Some examples of ‘applied’ research are:

1. Image–research.

2. Readership studies.

3. Public opinion research.

4. Pre-testing public relations materials.

5. Effect–research.

6. Identity–research.

7. Environmental analysis.

8. Content analysis.

9. Post-testing.

10. Quality control measurement.

This list of applied research subjects was the result of a membership survey in 1987 among IPRA members. The items are in order of importance according to the responses.

These projects have been elaborated by educators and researches in many countries, egg, USA, the Philippines, India, The Federal Republic of Germany, The Netherlands, France, Denmark, Austria, etc.

They are partly based on previous communication research studies and traditions, such as ‘Gatekeeper’ research models, ‘Uses and Gratifications’ models, ‘Agenda Setting’ theories, ‘Cultural Indicator’ models, Linguistic studies, etc. Partly they are original, but strongly related to research studies in sociology, social psychology, economics, linguistics, etc.

The Reality of Public Relations Related Research

We are still in the early stages of a period of great ferment and excitement in public relations related research. One can base this view on the dramatic increase in research activity, which has been evident in the past few years.

On the academic front there area a number of new or modified theoretical arguments that have recently been advanced that merit the attention of public relations practitioners. In the industrial sector there is now a considerable amount of research work underway, both to obtain information that can be used for public relations planning and programme development purposes and to try to measure and evaluate the effectiveness of some of the work being done in the field.

For a complex combination of reasons, however, basic original research by public relations educators and public relations practitioners is far from the level the Commission would like to see.

As the USA-based ‘Commission on Public Relations Education’ reported in 1975:

‘Most public relations educators – not having attained the PhD level – have not been required to do such research, have not learned how to do it, or have not been interested in doing it. Most of them, indeed, are teaching skills courses that have little relationship to basic research.’

‘Public relations practitioners, on the other hand, generally have been too busy at their jobs to engage in basic research, not connected with specific public relations tasks.’

Now in 1990, the situation has been changed encouragingly. There are more important reasons why research has still not gained a central position in public relations education and public relations practice during the last years. At university level public relations research has in general not yet been recognised as important or fundamental. The exploration of this field is a very expensive task and only very few academic staff are capable of designing public relations research programmes. Besides that, the profession has not suggested challenging research objectives. These facts are due to the lack of insight into the interdependence of four basic elements: research, theory building, teaching and practice. The only way to remedy this state of affairs is to explore the relationships between them.

The last ten years have shown us how those who practise public relations are becoming increasingly dependent on research knowledge. There is a danger, however, that attempts to tie

academic programmes to the needs of the profession might result in applied research taking the place of basic research.

Encouraging graduate-level educational programmes with a specialisation in public relations should lead to an increase in public relations research.

We should, however, not close our eyes to the practical implications in elaborating public relations research and programmes.

At most universities with Masters and PhD programmes, public relations research programmes are integrated in the training of students. The first reason is the financial one: students are comparatively cheap employees. The second is that students should be familiar with basic research and techniques. The third is that students are confronted with the solution of practical problems by research so that they can learn how to use research successfully in their future career.

Cooperation between Academics and Practitioners

There is no doubt that there can be gaps between theory, education and practice. More work in the field of research should be carried out in close cooperation between universities and practitioners.

In industry, not enough attention is paid to some of developments and theories evolving from academic scholarship. This will change as more and more of us beyond the simple, descriptive opinion poll and become more heavily involved in exploratory and explanatory research assignments.

As our own work becomes more sophisticated it will be necessary to seek out the best minds–wherever they might be, in academia or in business–to obtain the best possible solutions to the research problems, which we face.

In turn, academians have often been remiss in not making their own work more understandable to practitioners and also in not making enough effort to determine how academic scholarship might be made more applicable to the problems of the real world. Just as it is important for practitioners to know about new trends in thinking in academic circles, so too is it important for professors of journalism, public relations, marketing and advertising to keep abreast of the problems faced and dealt with in the industrial sector.

The obvious handicap in all this, of course, is that academic publish and professionals do not. This arises because academics are rewarded for publishing while professionals are rewarded for carrying out confidential research.

Yet information and ideas can be productively and effectively exchanged between academics and the profession, even taking into consideration the vastly different circumstances and orientations in which they operate. One suggestion is the arranging of a series of informal small group dialogues between academic and commercial researchers to explore in some depth the different types of work in which they are engaged and to discuss some of the broader implications of research for the discipline as a whole.

There is an enormous amount of work required to transfer the understanding of other disciplines into the public relations arena. It requires either practitioner-academics to immerse themselves in other relevant disciplines, or brought-in academics being persuaded to focus directly on the needs of public relations education. This is large an issue for educators as specific public relations research.

7. EVALUATING THE EFFECTİVENESS OF PUBLİC RELATIONS

Unless we can evaluate accurately the effectiveness of our work in public relations, we shall fail to achieve the credibility we need.

Very little research carried out for public relations purposes, and little of that attempts to measure effects or results. Much research is carried out in universities, but most of this is long term and not directed specifically at public relations issues.

It is desirable that all public relations budgets should include provision for initial analysis research and for action to monitor the effectiveness of programmes.

The following are some of methods used to measure this effectiveness:

1. Benchmark Surveys and Communications Audits.

2. Media quality and quantity assessment.

3. Periodic management reviews.

4. Perception research.

5. Supplier and customer interrogation.

6. Government reaction.

7. Environmental monitoring.

8. Image–change research.

9. Employee Exit–interviews.

10. Analysis of complaints.

11. Post-testing.

12. Analysis of spontaneous applications.

Measuring the effectiveness of public relations programmes is never easy because it is often difficult to isolate the results of public relations activity from environmental or other effects. Where, however, specific objectives are the goal it should be possible to measure reasonably accurately whether these objectives have been realised partially or fully. The time scale must be taken into account in this assessment.

The importance of pure and applied research has been emphasised in chapter 6 but evaluation is a more specific activity since it is designed to measure the results of planned effort. However, the results of general research can often be helpful in measuring the effectiveness of any particular campaign.

The real problem is undoubtedly financial. If universities are to be expected to conduct research studies of a kind, that, while developing a more scientific basis, are at the same time relevant to practical decision making, they will require very substantial funding as well as access to confidential information. To be successful such research would require the joint involvement of academics, professionals and organisations interested in this kind of research data.

An increase in doctoral level programmes at universities could not only help to provide more guidance on evaluation problems, but would also help to extend and upgrade public relations education generally. If more studies were to emerge, they would be valuable resource material available to public relations consultancies, corporations, government agencies and others interested in evaluation research.

Unless public relations becomes more analytical, not just quantitatively but also qualitatively, we shall not be on firm ground in assessing results.

A more holistic approach is required. An example of which would be case studies of the way in which corporations have responded to issues arising out of the environment. There is a need to

discover the relationships between variables and results in the laboratory and those in real world conditions. But we should think more about policy-oriented research if we wish the public or private sectors to pay the cost, let alone understand the relevance.

An interim stage is to open up lines of communication and cooperation with various academic faculties. This can take the form of research workshops or symposia, a recurring theme of this paper. Evaluation is a problem that has to be solved if we are to achieve ultimate credibility. This will require further investigation and sharing of knowledge.

The breadth of the field of public relations means that any research project must be very specific in the terms of what is being measured. The variables must be clearly understood, and it must be appreciated that awareness is not necessarily the same as change of attitude.

There is a great need for publication of case histories, which need to be more detailed than the usual rather descriptive case studies, which are generally available.

The IPRA Golden World Awards sponsored by Nissan, and similar case study competitions in many countries, will provide increasingly the case study material, which is a valuable resource in teaching.

8. RECOGNITION, ACCREDATION AND ENTRY CONDITIONS

Fundamental to the whole problem of developing criteria for the accreditation of public relations programmes is the defining of the body of knowledge upon which the criteria should be based.

There is no all-embracing theory to tie the field together. It does not create a conceptual framework. In the meantime, it is the Commission’s contention that all programmes should have many different courses in public relations, an internship, more than one instructor with a professional as well as an academic background, guest lecturers from practice, a balance between theory and concepts and practice, monitoring of the success of graduates in public relations careers and support materials–books and case studies of high quality. Computer-aided materials and other electronic material will become of increasing importance.

It is recommended that an ideal standard of acceptance for accreditation should be to provide students with a common body of knowledge in public relations. Programmes should include instruction in management science and analytical methods; human relations; motivation and attitudes studies and communication; and the external environment in which different organisations operate.

The questions of entry requirements, levels of education and standards of practice are often confused with considerations of our own status, which is inward looking and relates to our own personal aspirations.

We should candidly appraise and reassess the relevance of the public relations function to contemporary society. It is important for practitioners to possess the right combination of experience, personality, temperament and academic qualification to earn credibility. Recognition of public relations education must be earned but practitioners could do much more to enhance the reputation of various programmes. The impressive growth record of recent courses in places such as the Netherlands, Spain, New Zealand and Australia should make it easier than some pessimists believe.

In 1981, the American Council on Education in (ACEJ), the officially recognised USA body for accrediting schools of journalism was renamed. It is now known as the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (ACEJMC), extending its accrediting powers

to include the latter schools. ACEJMC is also empowered to accredit public relations course sequences in such schools.

To date, 25 public relations sequences have received ACEJMC accreditation. There have been some critics in the USA of this seemingly low rate of accreditation, citing the existence of some 300 colleges and universities, which currently offer such instruction.

Another example is the situation in the Netherlands. Since 1968 the Government recognises the examination for the ‘Basic Diploma NGRP’. Candidates are examined under supervision of a representative of the Government. This model comparable to the situation in Switzerland.

At the level of University education of the Government and the professional organisation, The Dutch Public Relations (NGPR) are officially working together in the accreditation of the official chair for Public Relations theory (since1978) of the so called post-academic education. That last type of education has been possibly by a special law. This law covers both financial and qualitative aspects (level of the courses, where it should be thought, entrance to the course, etc) of post-academic education. In the Federal Republic of Germany this type of post-academic education started in 1977.

In Great Britain, the Instate of Public Relations will be introducing an examination requirement for membership from 1992.A similar requirement has operated inner Zealand since 1984.

The situation in Europe may be changed by the attempts at harmonisation of all types of professional practice from 1 January1993.

It is too early to judge how, or if, further relations practice will be affected.

The ideal entry requirements for the profession, as envisaged by the Commission, are given in chapter 4.

9 RECOMMENDATION

1. Public relations full-time education should be offered at leading universities and other higher education institutions at first degree, postgraduate and doctoral levels. These degrees will equip successful students to fill positions in the profession at different level.

2. Public relations should be taught as an interdisciplinary subject with both academic and professional emphases.

3. Courses should be taught by individuals with substantial experience and sound understanding of both academic and professional aspects of the field.

4. It is highly desirable for a public relations programme at a university to have a strong faculty team with complementary strengths and adequate physical and library resources.

5. Sound ethical standards for students and practitioners should always be emphasised and correct professional attitudes and standards encouraged.

6. It is neither desirable nor necessary for public relations education to be uniform throughout the world. Rather is it essential that curricula should take into account local and national cultures, religions and indigenous conditions.

7. There should be integrated approach to programmes of education and professional advancement for those working in public relations. These educational opportunities should branch out into related disciplines.

8. Encouragement should be given to the provision of new texts, especially those dealing with specialised aspects of practise and research. The production of suitable electronic material should be encouraged in every way.

9. Public relations departments of universities should consider it their duty to cooperate with national public relations associations in the provision of short courses at varying levels.

10. UNESCO should be urged to continue their support for the series of regular educators’ meeting organised by IPRA in many different parts of the world. These have played an important part in the continuing development of public relations education.

11. IPRA council members and representatives of national and regional public relations associations should seek a dialogue with university bodies in their area to establish a rapport between the professional field and academia.

12. IPRA must offer to act as a clearinghouse between public relations bodies and university authorities.

13. Positive efforts should be made to bring about a continuing dialogue between academics and professionals for their mutual benefit.

14. Research, both pure and applied, should be encouraged in educational spheres and in practise.

15. Professional advancement programmes should be expanded in all countries.

16. There should be a regular interchange of information and ideas between public relations educators in different countries. This can be effective through IPRA world congresses. Educators’ meetings, the professional press and by direct contact.

17. CERP Education should be supported, as should all other regional educational foundations or associations in India, Latin America, North America, Africa and elsewhere.

18. Efforts should be increased to ensure that in business and management schools at university and other public relations is included in management education programmes, taught by qualified faculty or by experienced public relations practitioners on a visiting faculty arrangement.

Appendix 1

A RECOMMENDED CURRICULUM

The central circle of the wheel of education covers the theory and practice of public relations. Different colleges have established a curriculum, which is considered appropriate; bur considerable variation is possible within the general framework.

The report of the US Commission on Public Relations Education, which was published in 1987, included the results of an enquiry among 1,500 public relations practitioners and academics. Respondents were asked to comment on a typical curriculum and to rate their replies from I to 7, from ‘not essential’ at I to ‘most essential’ at 7.

The results were as follows:

Origins and Principles of Public Relations

6.27 Nature and Role of Public Relations: Definitions

6.10 Societal Forces Affecting Public Relations

4.87 History of Public Relations

The Public Relations Field

6.00 Duties of Public Relations Practitioners

5.53 Career-long Professional Development

5.53 The Public Relations Department

5.45 The Public Relations Counselling Firm

5.21 Qualifications, Education and Training Needed

Public Relations Specialisations

6.43 Publicity and Media Relations

6.01 Community Relations

6.00 Employee Relations

5.71 Consumer Relations

5.29 Financial/Shareholder Relations

5.26 Public Affairs/Lobbying

4.93 Fund-raising/Membership Development

4.50 International Public Relations

Public Relations Research

6.12 Public Relations Research/Designs/Processes/Techniques

5.92 Public Opinion Polling/Surveys

5.74 Fact-finding/ Applied Research

5.47 Observation/Performance Measurement

5.43 Social Audits/Communications Audits/Employee Audits

5.40 Issue Tracking

5.27 Focused Interviews/Focus Groups

5.22 Use of External Research Services/Consultants

5.11 Media Analysis/Clippings Analysis

4.56 Historical Research

Public Relations Planning

6.40 Setting Goals, Objectives, Strategies, Tactics

6.15 Audience Segmentation

6.07 Problem/Opportunity Analysis

6.01 Budgeting

5.87 Contingency / Crisis / Disaster Planning

5.60 Issues Management

5.52 Timetables/Calendaring

5.37 Assigning Authority / Responsibility

5.34 Planning Theory/Techniques/Models

5.16 Organisational Background/Philosophy /Culture

Public Relations Ethics and Law

6.22 Ethics and Codes of Practice, Public Relations and Other Professions

6.11 Credibility

5.91 Public Relations Law

5.20 Compliance, Regulatory Agencies, etc.

Public Relations Action / Implementation

5.98 Campaigns

5.70 Continuing Programmes – Personnel, Safety, Suggestions, etc.

5.60 One-time Incidents/Crises/Situations

5.52 Individual Actions by Public Relations

5.33 Individual Actions by Employer or Client

5.11 Meetings/Workshops/Seminars/Conventions, etc.

5.08 Other Special Events

Public Relations Communication

6.51 Planning, Writing, Producing and Delivering Print Communication to Audiences.

6.27 Planning, Writing, Producing and Delivering Audiovisual, Electronic, videotape and Multimedia Communication to Audiences

5.87 Employee/Internal Communication

5.78 New Public Relations Tools and Techniques

5.76 Message Strategy

5.71 Persuasion

5.68 Controlled (Advertising) v Uncontrolled (Publicity) Communication

5.62 Interpersonal Communication

5.52 Communication Theory/Concepts/Models

5.37 Layout and Graphics

5.28 Speech-writing/Speech-making/Speech Bureaux

5.12 Feedback Systems

4.84 Spokesperson Training

4.82 Propaganda

4.77 Photography and Filmmaking

4.66 Corporate/Graphics Identity

4.64 Working with Outside Suppliers

Public Relations Performance Evaluation / Measurement

6.27 Measuring Programme Effectiveness

6.13 Decision-making Based on Results (Planning)

6.12 Tools/Methods of Evaluation/Measurement

5.99 Setting Performance/Success Criteria

5.96 Reporting on Results of Public Relations Efforts

5.61 Measuring Staff/Public Relations Counsel Effectiveness

Appendix 2

TYPICAL PUBLIC RELATIONS CURRICULA

Public relations education is such a wide field that it is hardly surprising that there are many different models.

It is difficult to compare public relations programmes in different parts of the world because of the contrasting ways in which graduate and postgraduate degrees are organised and awarded.

In the USA. Great Britain and Australia public relations degree programmes are now usually independent, although interdisciplinary in content. In most other countries, public relations sequences are often a part of wider programmes, eg mass communication.

The following examples from a number of different countries emphasise the diversity of approach.

New Zealand

In 1984 the members of the Public Relations Institute of New Zealand (PRINZ) introduced membership of their institute by examination only.

Their Accreditation Examination was introduced with the assistance of Massey University Department of Human Resource Management. The special diploma course has matured into a well-organised programme at Massey University.

The course is an in-depth study of public relations theory and practice in New Zealand and overseas.

Special emphasis is placed on mass communication, employee relations, government and political public relations, and issues management.

There is a strong applied approach but the course also meets an increasing demand for theory and for research techniques. The underlying objective always is to heighten the student’s critical understanding of the communication process.

The course is taught in five modules. These are:

Module 1The Concept of Public Relations

Module 2 The Tools of Public Relations

Module 3 Public Relations in Practice I

Module 4 Public Relations in Practice II

Module 5 Public Relations and Society

Modules 1 and 2 are taught in the First Term;

Modules 3 and 4 in the Second Term; and

Module 5 in the Third Term.

University of South Alabama, (USA)

The Master of Arts degree in Communication at the University of South Alabama (Mobile, Alabama, USA) emphasises corporate and public communication. The programme provides educational opportunities for those who wish to specialise in public relations. Graduates will be prepared for upper level, administration and professional careers in: public relations, corporate communication, marketing, training and development, advertising, and communication research.

Beyond these professional careers, graduates of the programme electing to complete a thesis will be qualified to enter a doctoral programme in communication or public relations.

This programme is designed to meet the needs of both practitioners and scholars. The programme assumes students have mastered the various communication skills through previous study. An undergraduate degree in communication is required for entry as is previous course work in statistics. In unusual situations, an undergraduate degree in a related field can be substituted for students with significant working experience in corporate or public communication. Graduate instruction at South Alabama centres on the roles of public relations people in management, decision-making and problem solving. Classes have been designed to integrate theory and practice.

A culminating project moves either in the direction of an applied project or a hypothesis-based research project.

All MA degree students are required to take these three “core” courses:

Communication 500 Foundations of Graduate Study

Communication 502 Communication Theory

Communication 503 Communication Research Methods.

With the approval of their academic advisor, students select an additional eight courses to complete their degree programmes. Three of these courses may be from outside departments such as business marketing, management, sociology, political science or psychology.

In addition to the required core courses, communication instruction is provided in argumentation, persuasion, interpersonal communication, public relations administration, organisational communication, ethics and responsibility in communication, group communication, mass communication and communication technology systems.

University of Stirling (Scotland)

The Department of Business and Management at the University of Stirling developed in cooperation with IPRA, a unique one year Masters degree dedicated to the study of public relations. The programme is intended for those having a first degree or equivalent professional qualifications and / or substantial experience in the field of public relations. It is designed to develop the knowledge and skills required for a career in public relations by home and EEC students as well as for students from overseas.

The Programme

The course is a taught Masters degree mounted over two fifteen week semesters from September to May, and consists of a number of modules covering the range of knowledge and skills required by professionals in the field.

The programme provides a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of public relations and has been developed in cooperation with senior practitioners many of whom are also actively involved in the tuition of the programme.

Students who successfully complete the taught part of the programme qualify for the award of a Diploma. To qualify for the award of the Masters degree students must complete a dissertation or research project during period June to August. The dissertation topic is selected by the student in consultation with their tutors and is supervised by a member of staff with the appropriate expertise.

Programme Structure

Autumn Semester Core Units

Marketing Management, Business and Economic Environment, Communications I, Media Studies, Working with the Media, Public Relations Management, General Management.

Spring Semester Core Units

Public Relations Strategy, Advertising and Promotion, Communications II, Corporate Responsibility, Media practicals, Publishing studies.

Plus Two Electives from:

Financial Public Relations, Political Public Relations/Public Affairs, Audio- Video Production.

Summer Semester

Dissertation / Project.

The success of the full-time MSc programme led to the introduction of a three-year MSc in public relations by distance learning.

The University welcomes applications from suitably qualified men and women wishing to study for a PhD in public relations.

India Foundation for Education

The Public Relations Society of India (PRSI) has introduced a comprehensive system of public relations education through the new India Foundation.

The training syllabus is established by the requirements of the examination.

Approved Syllabus

Principles, scope and function of public relations; Historical perspective; The environment; Human behaviour; The various publics of public relations; the employee public; the investing public; special publics; the government; youth and the educational institutions; parent/teacher groups – grants/scholarships, labour unions, dealers and customers, the community; The counselling role of public relations, the communication role of public relations; Media, press, the printed word, photography, advertising, exhibition and fairs, audiovisual, the spoken word; Other

tools and techniques; Planning and implementing a public relations campaign; Specialised public relations, financial public relations, public relations within the organisation, public relations for govt/legislators, public relations for the public sector; Organisation, budgeting, etc; Research and evaluation; Public relations and special groups; Public relations as a profession.

Mount St Vincent University, Nova Scotia (Canada)

Bachelor of Public Relations Degree

This programme is designed to answer the need for university-trained public relations professionals in Canada. Students receive instruction in a variety of liberal arts subjects, communication techniques, public relations theories, practices and management. Graduates are qualified to take up positions in public relations, public affairs and information services in business, government, media, educational and non-profit institutions and consulting firms.

Course Requirements

Public Relations 100 Introduction to Public Relations half unit

Public Relations 105 Introduction to Mass Communications I half unit

Public Relations 112 Writing and Reporting I half unit

Public Relations 200 Advanced Public Relations half unit

Public Relations 205 Introduction to Mass Communications II half unit

Public Relations 212 Writing and Reporting II half unit

Public Relations 215 Audio-Visual Communication half unit

Public Relations 307 The Role of Design in Public Relations half unit

Public Relations 311 Advanced Public Relations Writing half unit

Public Relations 312 Print Media Planning and Writing half unit

Public Relations 315 Radio and Public Relations half unit

Public Relations 325 Television and Public Relations half unit

Public Relations 407 Public Relations Management I half unit

Public Relations 408 Public Relations Management II half unit

Public Relations 409 Research Methods for Public Relations Practice half unit

University of Roskilde, (Denmark)

The study of public relations leads to a full academic degree in the subject. The education consists of 11 modules, the total length being 5 1/2 years. The public relations profile is ensured especially through the writing of a thesis in public relations, and through an obligatory internship in an organisation. The main bulk of studies take place in project-oriented studies in groups of normally 4 or 5 students. Emphasis is out on the students’ ability to formulate and analyse problems, and to work out solutions to them.

Public relations at Roskilde University comprise a combination of two major subjects. After 2 years of basic training in the social sciences, the students continue with 2 modules of business economics and management with 2 modules of communication studies. After these 4 modules there is an internship period of t year, followed by the thesis, which integrates a business module with communication module.

The modules must be studied in the following order:

Basic education

2 years: 2 projects in macro-economics, politology, and sociology. The two projects must cover the three items.

Degree Programme

3rd and 4th year: 2 modules of business economics and 2 modules of communication.

Final 1 1/2 years:

– 1 internship consisting of a 3 months’ stay in an organisation resulting in a written report.

– 1 thesis in public relations combining management and organisationa1 communication.

Helsinki University, (Finland)

The University of Helsinki offers a specialised programme leading to a MSc degree in Communications.

The programme is a Master’s degree. The training takes 4 to 6 years and can be divided into three main cycles:

1 Introduction to corporate communication and public relations as well as communication methods and regulations.

2 Introduction to communication theories and research as well as to different trends of public relations research.

3 Methods of communication research, personal and interaction group communications and mass communication theories. Advanced courses both in interaction communication and mass communication as well as in international communication.

The programme is completed by the pro graduate theses and final examination.

Postgraduate degrees (licentiate and doctorate) can be achieved by completing a larger research project and dissertation.

Bachelor Degree Programmes in Britain

The influence of IPRA Gold Paper No 4 has helped to facilitate the introduction of three new modular BA Honours degrees in public relations in Great Britain.

These courses are available at College of St Mark and St John (University of Exeter); Bournemouth Polytechnic and Leeds Polytechnic.